JAN LIEVENS

Leiden, 1607-Amsterdam, 1674

SAINT JOHN THE EVANGELIST

Circa 1629

Black and white chalk, on grey prepared paper

196 x 114 mm

Provenance: London, art market (attributed to Pieter Lastman); Sale, Amsterdam, Christie’s, 14 November 1994, lot 46 (as Dutch school, first half of the 17th century); sale, Amsterdam, Christie’s, 1 November 1996, lot 116; Bilbao, private collection.

Literature: Bernhard Schnackenburg, trad. Kristin Lohse Belkin, Jan Lievens: Friend and Rival of the Young Rembrandt with a Catalogue Raisonné of His Early Leiden Work 1623-1632, Petersberg, Michael Imhof Verlag, 2016, cat. 99, pp. 282-283 (repr.).

Jan Lievens, son of a Leiden embroiderer, showed artistic talent at an early age. After initial training in his native city, the young painter was an apprentice, between the ages of ten and twelve, in Pieter Lastman’s atelier in Amsterdam. Back in Leiden, in 1628 he met Constantijn Huygens, a man of letters, patron of the arts and secretary to two Princes of Orange; this proved to be a turning point in Lievens’s career and led to international aspirations. He moved to London in 1632, and to Antwerp three years later. He then returned to the Netherlands, where he undertook various prestigious commissions in The Hague and Amsterdam.1

Although 17th- and 18th-century literature ensured that Lievens’s work was remembered, in the 19th century he was overshadowed by the prestige of his famous contemporary Rembrandt. Both had been pupils of Lastman, four years apart – Lievens first – before the “two young and noble painters from Leiden” became friends and engaged in an artistic dialogue, as is attested to by their many stylistic affinities during the second half of the 1620s.2 It was not until the 1970s that Lievens’s personal style regained recognition through the work of Rudolf E. O. Ekkart, Rüdiger Klessmann and Sabine Jacob, which led to the first monographic exhibition at the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum in Brunswick, in 1979.3

Subsequent studies by Werner Sumowski and Pieter Schatborn added to our knowledge of Lievens’s work, particularly his prints and drawings, until an international exhibition in 2008 brought wider and long-overdue awareness of the artist’s outstanding talent.4 Coinciding with the exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum in 2011, studies by Gregory Rubinstein were instrumental in distinguishing between the graphic works of Lievens and Rembrandt from the late 1620s and up to Lievens’s departure for London in 1632; the similarities made it particularly difficult to tell them apart in studies of figures combining black and red chalk.5

Attributed to Lievens by Sumowski and Schatborn, then published by Bernhard Schnackenburg in 2016, our Saint John the Evangelist can be dated to his years in Leiden; Schnackenburg dates it more precisely to circa 1629. For a long time, it was associated with a second drawing – the whereabouts of which are no longer known – depicting Saint John with a variation in the position of his arms. Both are stylistically very close to a study for a Saint Peter, now in the Albertina Museum, Vienna, which was first published in 1932. That, too, is in black chalk and possesses the same monumental character despite its smaller dimensions (ill.).6

Preparatory drawings relating directly to a print or painting are relatively rare in the artist’s oeuvre, and these sheets are not an exception. They may be studies in their own right, recalling Odoardo Fialetti’s engravings of religious figures, published in Venice in 1626.7

1 These included the decorations in the Oranjezaal in the Huis ten Bosch, the royal summer palace of the House of Orange near The Hague, and the Burgomaster’s chamber in the Amsterdam Town Hall.

2 The phrase “two young and noble painters from Leiden” was used by Constantijn Huygens, see Jan Lievens: A Dutch Master Rediscovered, exhib. cat. (Washington, National Gallery of Art, 26 October 2008-11 January 2009, Milwaukee Art Museum, 7 February-26 April 2009, Amsterdam, Rembrandthuis, 17 May-9 August 2008), Arthur K. Wheelock (ed.), Washington|New Haven|London, National Gallery of Art|Yale University Press, 2008, pp. 286-287.

3 Ibid., pp. viii-ix.

4 Cf. n. 2. Werner Sumowski, trad. Walter L. Strauss, Drawings of the Rembrandt School, vol. VII, New York, Abaris Books, 1983; Jan Lievens (1607-1674), prenten en tekeningen, exhib. cat. (Amsterdam, Museum het Rembrandthuis, 5 November 1988-8 January 1989), Peter Schatborn (ed.), Amsterdam, Rembrandthuis, 1988.

5 Drawings by Rembrandt and his pupils: telling the difference, exhib. cat. (Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 8 December 2009-28 February 2010), Holm Bevers (ed.), Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009; Gregory Rubinstein, “Brief Encounter: the Early Drawings by Jan Lievens and Their Relationship with Those of Rembrandt”, Master Drawings, vol. XLIX, no. 3, 2011, pp. 352-370; Gregory Rubinstein, “Three Newly Identified Figure Drawings by Jan Lievens” in Liber Amicorum Dorine van Sasse van Ysselt, Charles Dumas (ed.), The Hague, Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie, 2011, pp. 51-55.

6 Bernhard Schnackenburg, trad. Kristin Lohse Belkin, Jan Lievens: Friend and Rival of the Young Rembrandt with a Catalogue Raisonné of His Early Leiden Work 1623-1632, Petersberg, Michael Imhof Verlag, 2016, cat. 98, pp. 281-282 and cat. 100, p. 283.

7 Ibid., p. 102.

Jan Lievens, Saint Peter, black chalk, white chalk highlights, 296 x 182 mm, Vienna, Albertina Museum, inv. 8906.

ANTON CLEMENS LÜNENSCHLOSS

Düsseldorf, 1678-Würzburg, 1763

ERUPTION OF VESUVIUS FROM 5 TO 13 JUNE 1717

1717

Pen and black and grey ink, grey wash

510 x 720 mm [the composition]

534 x 738 mm [the sheet]

Watermark: a Strasburg lily (h. 130 mm).

The life and work of Anton Clemens Lünenschloss, court painter to the Prince-Bishop of Würzburg from 1719 until his death in 1763, are documented in a collection of 1300 drawings in the Martin von Wagner Museum.1 After studies in Düsseldorf and Antwerp, Lünenschloss spent almost twenty years in Italy under the protection of the Elector of the Rhine Palatinate. He moved to Rome in 1703, after spending time in Venice and Florence, and attended the Academy of Saint Luke and, in all likelihood, the atelier of Carlo Maratti.2 He then lived in Naples from 1708 to 1717, where he spent most of his time copying the great frescoes of Giovanni Lanfranco, Luca Giordano and Francesco Solimena, as the collection in the Martin von Wagner Museum attests. In Würzburg, he decorated ceilings for the Residenz from the 1720s onwards, before Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s famous contribution shortly after 1750.3

From his stay in Naples, the Martin von Wagner Museum holds a sheet with two landscapes drawn en plein air − perhaps, judging by the crease in the paper, a page from a sketchbook (ill. below). It is executed in an economical light-brown wash and is reminiscent of French or Dutch landscape painters active in Rome in the mid-seventeenth century − Gaspard Dughet or Lünenschloss’s contemporary, Alessio de Marchis. Dated 1717, it depicts the Magdalene Bridge with Vesuvius, steam rising from its crater, in the background on the left and Sorrento on the right, with comments and captions in Italian and German.

And indeed, from April 1717 onwards, activity on Vesuvius intensified until the eruption the following June. Lünenschloss witnessed this impressive event, which he has depicted in the large-format drawing presented here. Although he must have completed the work in his studio, he captured the composition from a vantage point between Torre Annunziata and Trecase. He gives a very concrete description of the eruption, describing the two mouths of the volcano, the appearance of the lava and the direction of the various flows, all of which are precisely captioned in a cartouche.

While observing this natural phenomenon, Lünenschloss also witnessed the behaviour of the population, adding an element of social satire to his drawing: while the nobility and the bourgeoisie have flocked from Naples to gaze at the eruption, the rural inhabitants have had to abandon their homes, which have been devastated by the lava flows.4

Lünenschloss made a second, signed drawing of the 1717 eruption. The point of view is from a slightly more northerly direction and from further back, so the Magdalena Bridge can be seen in the background on the left.5 These two very finished works were probably produced for commercial reasons, as mementos for clients wishing to have a picture of the intriguing phenomenon.

1 Dorette Richter, Der Würzburger Hofmaler Anton Clemens Lünenschloß (1678-1763). Sondergabe des Historischen Vereins von Mainfranken für das Jahr 1939, Würzburg, Richard Mayr, 1939, pp. 1-2.

2 Ibid., pp. 7-8; Stefan Morét, « Ein deutscher Maler des 18. Jahrhunderts in Rom: Zeichnungen von Anton Clemens Lünenschloß für den Concorso Clementino der römischen Accademia di San Luca im Jahre 1706 », Marburger Jahrbuch für Kunstwissenschaft, no. 32, 2005, pp. 255-270.

3 Richter, op. cit., pp. 61 and ff.

4 The philosopher George Berkeley, who witnessed the 1717 eruption, commented thus in a letter to John Arbuthnot: “Three or four of us got into a boat, and were set ashore at Torre del Greco, a town situate at the foot of Vesuvius to south-west (…) The roaring of the volcano grew exceeding loud and horrible as we approached. (…) all which circumstances (…) made a scene the most uncommon and astonishing I ever saw (…) Imagine a vast torrent of liquid fire rolling from the top down the side of the mountain, and with irresistible fury bearing down and consuming vines, olives, fig-trees, houses; in a word every thing that stood in its way.” (Alexander Campbell Fraser, M. A., Life and Letters of George Berkeley, D. D.…, Oxford, The Clarendon Press, 1871, p. 80).

5 Bologna, Vigliotti Collection.

Anton Clemens Lünenschloss, Two landscapes in the environs of Naples, 1717, pen and brown ink, brown wash, 280 x 365 mm, Würzburg, Martin von Wagner Museum, inv. Hz 5546.

DOMENICO MORELLI

Naples, 1823-1901

STUDY OF ORIENTAL FIGURES

Circa 1877

Pen and brown ink, watercolour

225 x 316 mm

Signed lower right: “Morelli”.

Annotated on the reverse by Alfredo Schettini: “Aquerello originale di Domenico Morelli 1823-1901 / “Le orientali” / 18 giugno 1960 Alfredo Schettini”.

Provenance: Naples, Giuseppe Casciaro (1863-1941), painter and pupil of Domenico Morelli; his sale, Florence, Galleria d’arte|Associazione nazionale degli artisti, June 1942 (“Odalische”, no lot number), the sale stamp and the signature of his son Guido Casciaro on the reverse, top; sale, Naples, Galleria Giosi, May 1960, lot 173; Italy, private collection.

Literature: Carlo Hautmann, I Pittori napoletani dell’800 e di altre scuole nella “Raccolta Casciaro”, Florence, Galleria d’arte|Associazione nazionale degli artisti, 1942, [unnumbered] (“Odalische”).

Exhibition: Florence, Galleria d’arte|Associazione nazionale degli artisti (Piazza Pitti 15), 16 May-10 June 1942.

Domenico Morelli entered the Real lstituto di Belle Arti in Naples in 1836, at the age of thirteen.1 His career was inextricably linked to the Neapolitan institution, which he went on to reform in the late 1870s along with the painter Filippo Palizzi – his alter ego and “antithesis”. But he also became a leading artistic figure in Risorgimento Italy.2

In 1844, he won first prize in a painting competition and a grant that enabled him to continue his studies in Rome. But the revolutions of 1848, which reverberated throughout Italy and Europe, provided an opportunity for him to shake off the academic stranglehold of the Institute, whose principles were still based on a classical ideal inherited from the late eighteenth century. In 1851, he escaped from Bourbon Naples and moved to Florence, where in 1855 he achieved his first critical success with The Iconoclasts. This painting reflected the painter’s intention to “represent figures and things, not seen, but both true and imagined”, thus paving the way for a form of historical verismoin his work.3 4

The choice of historical and literary sources for Morelli’s works, as well as his compositions, were fundamentally influenced by his friendship with the historian and politician Pasquale Villari. The two men exchanged ideas throughout their lives. Villari, a freethinker, introduced Morelli to the works of Dante, Alessandro Manzoni and Giacomo Leopardi, as well as to English literature in the form of Shakespeare, Walter Scott and Lord Byron.

From the late 1860s, they turned their attention to Middle Eastern history and the Christian and Islamic religions. Morelli researched rigorously, reading Ernest Renan in particular, and acquiring objects from the East and photographs of Palestine from the painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema.5 But when he met Mariano Fortuny y Marsal in the early 1870s, his Oriental subjects began to pay less heed to historical references and became pretexts for purely formal studies.

In 1877 Morelli produced an Odalisque which was acquired by the collector Giovanni Maglione (ill. below).6 Our study of two oriental women is related to this painting, despite their variations and the different natures of the two images. The oil painting is infused with an atmosphere of seduction that is not present in the watercolour study, where the focus is more on the interplay of colour and light; the whiteness of the drapery on the figure in the foreground is superbly rendered from the blank reserve of the paper.7 The use of this technique harks back perhaps to the style of art in which Fortuny was so skilled.8

Drawing was an essential part of Morelli’s creative process, enabling him to translate his ideas into images. A whole generation of artists followed in his footsteps; they adopted the medium as well as his style, which is recognisable above all by the spontaneity of his use of pen and ink.

1 Costanza Lorenzetti, L’Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli (1752-1952), Florence, Felice Le Monnier, 1952, p. 256.

2 “Antithesis” : this was Costanza Lorenzetti’s expression (id.). On Morelli’s appointments as professor at the Istituto di Belle Arti in Naples and the reforms in 1878, ibid, pp. 128-133.

3 Domenico Morelli, “Filippo Palizzi e la scuola napoletana di pittura dopo il 1840. Ricordi” [second part], Napoli nobilissima: rivista di topografia ed arte napoletana, vol. X, no. VI, 1901, p. 82: “(…) io sentivo che l’arte era di rappresentar figure e cose, non viste, ma immaginate e vere ad un tempo (…)”.

4 Naples, Capodimonte, inv. PS74. See Domenico Morelli e il suo tempo: 1823-1901 dal romanticismo al simbolismo, exhib. cat. (Naples, Castel Sant’Elmo, 29 October 2005-29 January 2006), Luisa Martorelli (ed.), Naples, Electa, 2005, p. 18.

5 As testified by the photograph of his studio taken by the Alinari brothers after the painter’s death in 1905 (Florence, Archivi Alinari, photograph no. ACA-F-019160-0000).

6 Primo Levi l’Italico, Domenico Morelli nella vità e nell’arte, Rome|Turin, Roux e Viarengo, 1906, p. 212. The painting was subsequently part of the Wissinger collection in Munich, before being sold in London by Christie’s (“Ottomans and Orientalist Art”, 21 June 2000, lot 37).

7 Morelli probably acquired the paper for the work from an Amalfi papermill. It can be compared with a drawing on watermarked paper held in Turin (Domenico Morelli: il pensiero disegnato, exhib. cat. (Turin, Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, 20 December 2001-3 February 2002), Claudio Poppi (ed.), Turin, Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, 2001, cat. 50, p. 215, repr. p. 147) and watermarks in the drawings collection of the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Rome (Rita Camerlingo, Il Fondo Domenico Morelli: catalogo delle opere su carta, Rome, Edizioni di storia e letteratura, 2010, F02 and F03, p. 306, repr. p. 313).

8 For example, Landscape at Portici, Madrid, Museo del Prado, inv. D007418.

Domenico Morelli, Odalisque, 1877, oil on canvas, 925 x 1845 mm, current whereabouts unknown. © Christie’s.

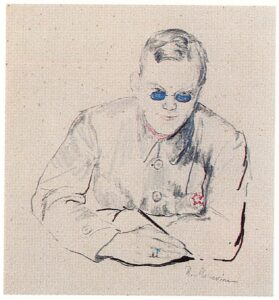

FILIPP ANDREEVIČ MALJAVIN

Kazanka (Samara, Russia), 1869-Nice, 1940

PORTRAIT IN BLUE SPECTACLES (A ‘BOLSHEVIK’)

Graphite, coloured pencils

445 x 308 mm

Filipp Maljavin spent a few years as a novice and icon painter at the Saint Panteleimonmonastery at the foot of Mount Athos before enrolling at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in Saint Petersburg in 1892; after his studies there, he became a student in Ilya Repin’s workshop.1 He was involved with ‘The World of Art’ (Mir iskusstva), a group founded in 1898 that spearheaded the secessionist system and played a significant role in shaping the Russian avant-garde. His friends Konstantin Somov and Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva were founder members, but Maljavin never became a member himself. At the turn of the century, he exhibited extensively in Russia and Europe: at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris, where he received a gold medal for Laughter – a painting acquired the following year by the Galleria Internazionale d’arte Moderna di Ca’ Pesaro; in 1901 he exhibited at the Venice Biennale; and, in 1903 and 1904, in Berlin.2

A few years later, he was one of a selection of Russian artists that Serge Diaghilev presented at the 1906 Salon d’Automne in Paris. Following Repin, his “rich and powerful” art, which combined his talents as both draughtsman and colourist, made a great impact on the French public.3 By the time he emigrated to Paris in 1924, Maljavin had already established a reputation and identity as a painter of the Russian peasant soul. That same year, Léonce Bénédite acquired a monumental canvas, Russian Peasant Women (ill. 1), for the Musée du Jeu de Paume. It had been presented in the artist’s first solo exhibition at the Galerie Charpentier.4

Maljavin also produced numerous portraits of Russian peasants as well as of high society figures (he was dubbed the “Slavic Besnard” by critic Raymond Bouyer).5 Around 1920, on the strength of the popularity of paintings in which he portrayed the faces of rural Russia, Maljavin was invited by the Bolshevik authorities to create a gallery of portraits of party members, and in particular the senior figures: Lenin, Leon Trotsky and Anatoly Lunacharsky.6

Although these drawings never became paintings, the artist guarded them faithfully after his exile:

“There is no disputing that [the portraits] are historically valuable – and even very much so! And the Bolsheviks themselves are hardly aware they are good! Personally I treat my own work with care, and these drawings particularly, (…) they are in a safe place.”7

Even Pablo Picasso owned a portrait of Lenin, as he confided to Mikhail Alpatov in 1960.8

There is a second portrait of our blue-spectacled model, wearing a Red Army uniform and decorated with a star (ill. 2). Although his identity is unknown, there seems to have been a certain complicity between the artist and his subject, whose face betrays a hint of playful provocation. In just a few strokes and with skilful use of coloured pencils, Maljavin has managed to capture the personality of this proud young member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party.

When Maljavin died, his studio became the property of his daughter Zoia Bounatian, before being acquired, for the most part, by a Monegasque dealer in the early 1950s. It is possible that this drawing, which more recently was part of an Italian collection, originates from the same source.9

1 Ivan Samarine, “Philip Andreyevich Maljavin : A Private Collection of Paintings from the Artist’s Studio” in the sale catalogue Philip Andreyevich Maljavin, Works from the Artist’s Studio, Sotheby’s, London, 19 February 1998, pp. 12-13.

2 Nicola Kozicharow, “Filip Maljavin in Emigration: Artistic Strategy and the Afterlife Secessionism”, Art History, vol. 42, no. 2, April 2019, pp. 307-309.

3 Arsène Alexandre, “L’exposition russe”, Le Figaro, 52nd year, series 3, no. 288, 15 October 1906, p. 5, quoted by Kozicharow, op. cit., p. 309 and n. 20, p. 328.

4 The Musée du Jeu de Paume acquired a second painting at the Salon du Franc in the Palais Galliera in 1926, Peasant Dance (Paris, musée d’Orsay, inv. RF 1977 247). Ibid., pp. 309 and 318.

5 Ibid., p. 314.

6 Ibid., p. 321-322.

7 Letter from Filipp Maljavin to his Czechoslovak dealer Dmitrii Nikitin, 28 January 1937, quoted in Kozicharow, op. cit., p. 325 and n. 96, p. 330.

8 Ibid., n. 4, p. 328.

9 Samarine, op. cit., p. 12.

Ill. 1. Filipp Andreevič Maljavin, Russian peasant women, 1902, oil on canvas, 1975 x 3047 mm, Paris, musée d’Orsay, inv. RF 1977 246.

Ill. 2. Filipp Andreevič Maljavin, Portrait of a Bolchevik, graphite, coloured pencils, 430 x 310 mm, whereabouts unknown (sale, Sotheby’s, London, 19 February 1998), lot 268).

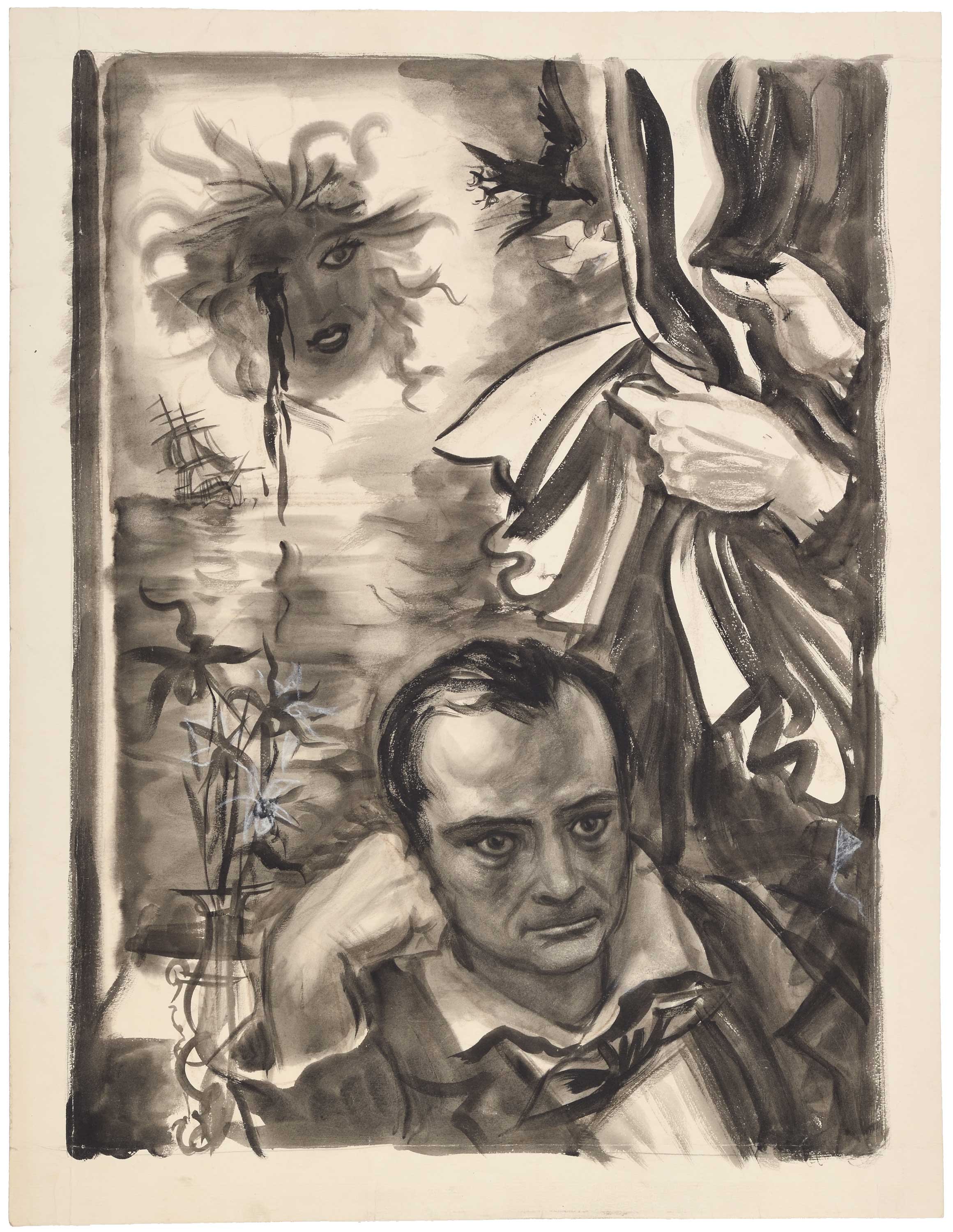

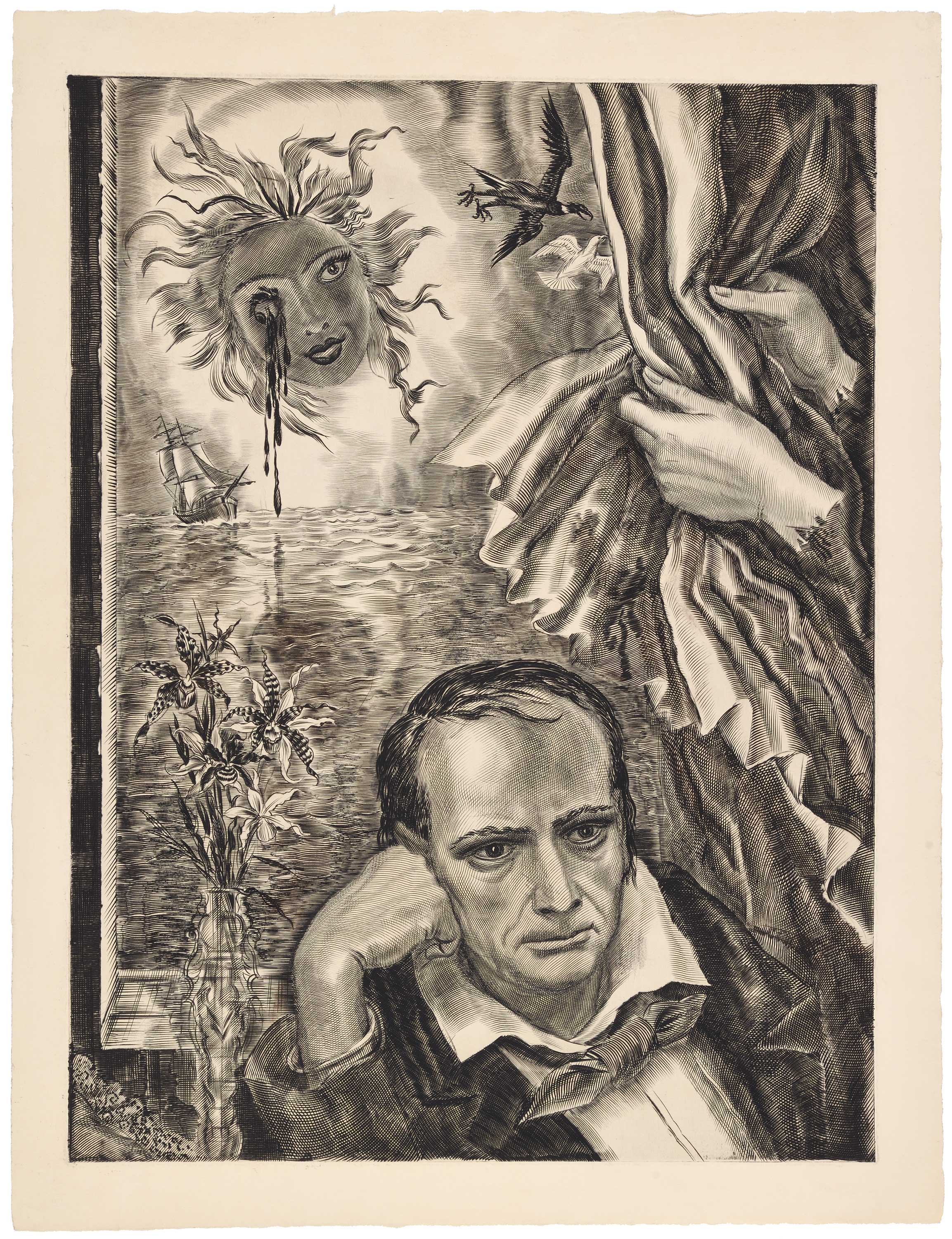

ALBERT DECARIS

Sotteville-lès-Rouen, 1901-Paris, 1988

PORTRAIT OF CHARLES BAUDELAIRE

Brush and black ink, white chalk

590 x 435 [the composition]

657 x 503 mm [the sheet]

Watermark: “PAPETERIES L.C.B. PÂTE ‘J.L BLACONS’”.

PORTRAIT DE CHARLES BAUDELAIRE (I)

Engraving

580 x 435 mm [the platemark]

657 x 503 [the sheet]

Watermark: “B F K Rives”.

Literature: Isabel Boussard-Decaris and Jean-Marc Boussard, Decaris le Singulier, Ollioules, Les Editions de la Nerthe, 2005, cat. op. 687, p. 212.

Although Albert Decaris is one of the leading figures of original engraving in the 20th century, towards the end of his life, the artist confessed that he had become an engraver “by chance”.1

In 1915, Decaris enrolled at the École Estienne, where they mainly taught reproductive engraving. After that, he moved on to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where, in 1919, he won the Prix de Rome for engraving, a bursary which enabled him to become a pensionnaire at the Villa Medici in November of the same year. He spent several years working and studying there, and became friends with the sculptor Alfred Janniot, who was close to the artists known collectively, along with Jean Dupas, as the Bordeaux school.

From the 1930s, when luxury art books came into vogue, Decaris produced illustrations for collectors’ editions. Over the course of his career, he illustrated a wide range of texts, including works by Shakespeare, Cervantes and Chateaubriand, and poems by Pierre de Ronsard, André Chenier and Verlaine.2 At the same time, he produced hundreds of engraved compositions, mostly large plates, ranging in size from Raisin (50 x 64 cm) to Grand Aigle (74 x 105 cm). Decaris also engraved more than 500 designs for postage stamps.

Men of letters feature prominently in Decaris’s gallery of engraved portraits, 19th century French Romantic poets in particular (Alfred de Vigny, Gerard de Nerval, Victor Hugo, Rimbaud and Verlaine). He made two large copperplate engravings, each slightly different, of Baudelaire.3 Both are bust-length depictions of the writer, in pensive, melancholic mood, standing in front of a window overlooking the sea – an evocation of his famous poem L’Invitation au voyage. The sketch for the portrait of Baudelaire, painted in broad brushstrokes in the format of the print, establishes all the motifs of the final composition. It has been reproduced on the plate without any intermediate stages or corrections, demonstrating the artist’s consummate technical skill. His fine, precise chiselling has produced subtle reliefs and rich blacks in the print.4

1 Decaris, gravures et aquarelles, exhib. cat. (Paris, Musée de la Poste, 13 juin-13 septembre 1981), Paris, Musée de la Poste, 1981, [n. p.].

2 Pierre-Louis Martin, « Albert Decaris : l’œuvre gravé de bibliophilie », Revue française d’histoire du livre, 60e année, nouvelle série, no. 70-71, 1991, p. 85 and ff.

3 Isabel Boussard-Decaris and Jean-Marc Boussard, Decaris le Singulier, Ollioules, Les Editions de la Nerthe, 2005, cat. op. 687 and 689, p. 212.

4 “Entretien avec Albert Decaris” in Albert Decaris, graveur de la légende napoléonienne, Paris, Bibliothèque Marmottan|Institut de France – Académie des Beaux-Arts, 1987, [n. p].