Giacomo del Po

AT THE MUSEO E REAL BOSCO DI CAPODIMONTE IN NAPLES

GIACOMO DEL PO

Rome, 1652-Naples, 1726

STUDY FOR THE GREAT DOOR OF THE MONASTERY OF SAN GREGORIO ARMENO IN NAPLES (RECTO)

SKETCH OF THE GREAT DOOR WITH MEASUREMENTS (VERSO)

Circa 1715-1719

Pen and brown ink, grey wash (recto)

Pen and brown ink (verso)

434 x 290 mm

Various measurements (in palms), inscribed by the artist (?); annotated bottom centre: “Giacomo del Pò.”

Watermark: a quadruped in a circle surmounted by a “P” (h. 63 mm).

Provenance: Émile Calando Collection, his mark bottom centre (L. 837); Sale, London, Sotheby’s, 13 December 2001, lot 24; Rome, Giancarlo Sestieri Collection.

Born in Rome and taught by his father, Pietro del Po, a painter and engraver from Palermo but Neapolitan by adoption, Giacomo began his career as a member of the Academy of St Luke in 1674. The following year, he was appointed as a teacher of notomia (“anatomy”) at the Academy. In 1683, the del Po family returned to Naples. As well as producing small paintings for collectors on canvas or copper, Giacomo del Po received a great many commissions for paintings, on canvas or as frescoes, for religious buildings and private palaces. At the beginning of the 18th century, he was one of the most prominent painters in this field in Naples, alongside Francesco Solimena and Paolo de Matteis. His career reached its apogee in 1723 when he was commissioned by Eugene of Savoy to paint the ceilings of the Upper Belvedere Palace in Vienna.

Giacomo del Po’s work was an interesting blend of the Roman style of Giovanni Battista Gaulli and Carlo Maratti, the Neapolitan fresco tradition exemplified by Luca Giordano, and the colours of the Genoese Baroque as typified by Gregorio de Ferrari. He incorporated illusionist elements, in particular figures in grisaille, and in so doing devised a formula that was to prove highly successful in the city of Naples. The painting for the great doorway of the Benedictine monastery of San Gregorio Armeno in Naples, dates from between 1715 and 1719,1 and is one of del Po’s mature masterpieces (ill. below).

Although the overall structure of the composition is unchanged, the preparatory drawing indicates a number of differences from the final work, including an alternative form for the medallion in which St Benedict is depicted. The drawing was probably made for submission to the commissioning parties. The postures of the figures have mostly been altered, while certain motifs have been changed. This is the case of the putti positioned above the hatches where the nuns, being careful to comply with the rule of seclusion, would deposit food for the poor. This activity explains the artist’s initial choice of the pelican, bottom left – a Christ-like symbol of giving.

Technically and stylistically, this sheet is very close to the drawing in the Cooper Hewitt Museum, which was a preparatory study for the monument in honour of Giacomo and Giovanni Domenico Milano in the church of San Domenico Maggiore in Naples. That drawing was dated around 1712.2 In both drawings, Del Po has used grey wash to indicate shadows and shading, thus creating an illusion of three-dimensionality which he would subsequently incorporate into the fresco.

Il Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte in Naples has acquired Giacomo del Po’s drawing in 2025.

1 Daniel Rabiner, « Giacomo del Po », Dizionario biografico degli italiani, vol. XXXVIII [Della Volpe-Denza], Roma, Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1990, ad vocem ; Marina Causa Picone dates the painting of the great doorway around 1711-1715 (see Marina Picone, « Per la conoscenza del pittore Giacomo del Pò », Bolletino d’arte, year XLII, serie IV, 1957, no. 2, pp. 163-172, no. 3-4, pp. 310-311) and Nicolas Spinosa in 1712 (see The Golden Age of Naples: Art and Civilization under the Bourbons, 1734-1805, exh. cat., The Detroit Institute of Arts, 11 August-1st November 1981, The Art Institute of Chicago, 16 January-8 March 1982, 2 vols., Detroit, The Detroit Institute of Arts, 1981., vol. I, p. 136).

2 New York, Cooper Hewitt Museum, Smithsonian Institution, inv. 1901-39-2173. See The Golden Age of Naples, op. cit., vol. II, cat. 91, pp. 266-267.

Present-day view of the great door of the San Gregorio Armeno monastery in Naples. © Soprintendenza per i Beni artistici e storici di Napoli e provincia|Fabio Speranza.

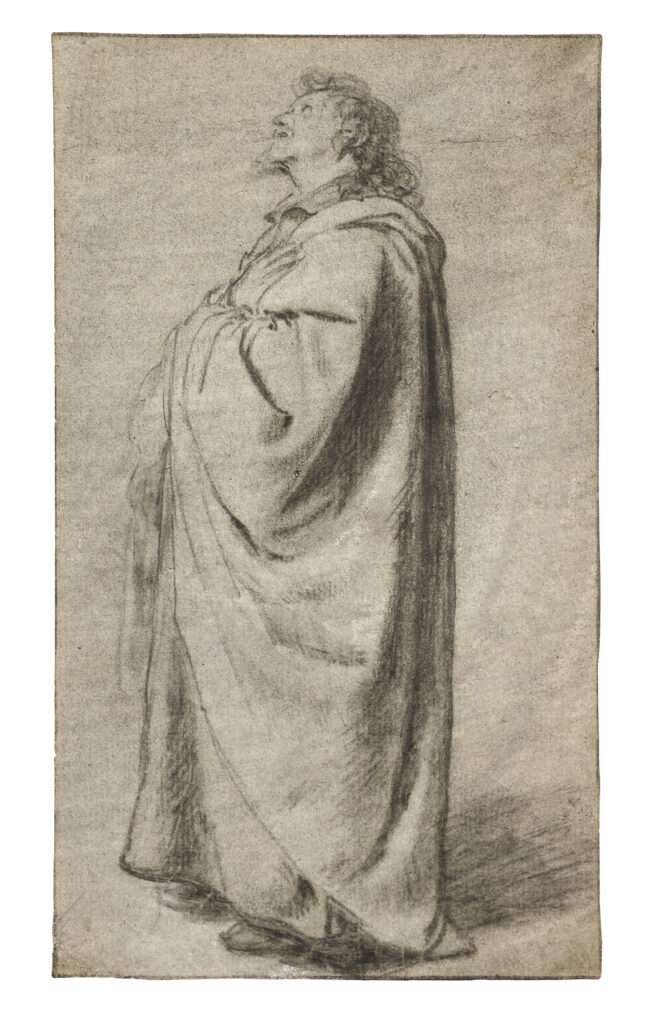

JAN LIEVENS

SAINT JOHN THE EVANGELIST AT THE RIJKSMUSEUM OF AMSTERDAM

JAN LIEVENS

Leiden, 1607-Amsterdam, 1674

SAINT JOHN THE EVANGELIST

Circa 1629

Black and white chalk, on grey prepared paper

196 x 114 mm

Provenance: London, art market (attributed to Pieter Lastman); Sale, Amsterdam, Christie’s, 14 November 1994, lot 46 (as Dutch school, first half of the 17th century); sale, Amsterdam, Christie’s, 1 November 1996, lot 116; Bilbao, private collection.

Literature: Bernhard Schnackenburg, trad. Kristin Lohse Belkin, Jan Lievens: Friend and Rival of the Young Rembrandt with a Catalogue Raisonné of His Early Leiden Work 1623-1632, Petersberg, Michael Imhof Verlag, 2016, cat. 99, pp. 282-283 (repr.).

Jan Lievens, son of a Leiden embroiderer, showed artistic talent at an early age. After initial training in his native city, the young painter was an apprentice, between the ages of ten and twelve, in Pieter Lastman’s atelier in Amsterdam. Back in Leiden, in 1628 he met Constantijn Huygens, a man of letters, patron of the arts and secretary to two Princes of Orange; this proved to be a turning point in Lievens’s career and led to international aspirations. He moved to London in 1632, and to Antwerp three years later. He then returned to the Netherlands, where he undertook various prestigious commissions in The Hague and Amsterdam.1

Although 17th- and 18th-century literature ensured that Lievens’s work was remembered, in the 19th century he was overshadowed by the prestige of his famous contemporary Rembrandt. Both had been pupils of Lastman, four years apart – Lievens first – before the “two young and noble painters from Leiden” became friends and engaged in an artistic dialogue, as is attested to by their many stylistic affinities during the second half of the 1620s.2 It was not until the 1970s that Lievens’s personal style regained recognition through the work of Rudolf E. O. Ekkart, Rüdiger Klessmann and Sabine Jacob, which led to the first monographic exhibition at the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum in Brunswick, in 1979.3

Subsequent studies by Werner Sumowski and Pieter Schatborn added to our knowledge of Lievens’s work, particularly his prints and drawings, until an international exhibition in 2008 brought wider and long-overdue awareness of the artist’s outstanding talent.4 Coinciding with the exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum in 2011, studies by Gregory Rubinstein were instrumental in distinguishing between the graphic works of Lievens and Rembrandt from the late 1620s and up to Lievens’s departure for London in 1632; the similarities made it particularly difficult to tell them apart in studies of figures combining black and red chalk.5

Attributed to Lievens by Sumowski and Schatborn, then published by Bernhard Schnackenburg in 2016, our Saint John the Evangelist can be dated to his years in Leiden; Schnackenburg dates it more precisely to circa 1629. For a long time, it was associated with a second drawing – the whereabouts of which are no longer known – depicting Saint John with a variation in the position of his arms. Both are stylistically very close to a study for a Saint Peter, now in the Albertina Museum, Vienna, which was first published in 1932. That, too, is in black chalk and possesses the same monumental character despite its smaller dimensions (ill. below).6

Preparatory drawings relating directly to a print or painting are relatively rare in the artist’s oeuvre, and these sheets are not an exception. They may be studies in their own right, recalling Odoardo Fialetti’s engravings of religious figures, published in Venice in 1626.7

The Rijksmuseum of Amsterdam has acquired Jan Lievens’s drawing in July 2025 on the occasion of the Trois Crayons exhibition in London.

1 These included the decorations in the Oranjezaal in the Huis ten Bosch, the royal summer palace of the House of Orange near The Hague, and the Burgomaster’s chamber in the Amsterdam Town Hall.

2 The phrase “two young and noble painters from Leiden” was used by Constantijn Huygens, see Jan Lievens: A Dutch Master Rediscovered, exhib. cat. (Washington, National Gallery of Art, 26 October 2008-11 January 2009, Milwaukee Art Museum, 7 February-26 April 2009, Amsterdam, Rembrandthuis, 17 May-9 August 2008), Arthur K. Wheelock (ed.), Washington|New Haven|London, National Gallery of Art|Yale University Press, 2008, pp. 286-287.

3 Ibid., pp. viii-ix.

4 Cf. n. 2. Werner Sumowski, trad. Walter L. Strauss, Drawings of the Rembrandt School, vol. VII, New York, Abaris Books, 1983; Jan Lievens (1607-1674), prenten en tekeningen, exhib. cat. (Amsterdam, Museum het Rembrandthuis, 5 November 1988-8 January 1989), Peter Schatborn (ed.), Amsterdam, Rembrandthuis, 1988.

5 Drawings by Rembrandt and his pupils: telling the difference, exhib. cat. (Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 8 December 2009-28 February 2010), Holm Bevers (ed.), Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009; Gregory Rubinstein, “Brief Encounter: the Early Drawings by Jan Lievens and Their Relationship with Those of Rembrandt”, Master Drawings, vol. XLIX, no. 3, 2011, pp. 352-370; Gregory Rubinstein, “Three Newly Identified Figure Drawings by Jan Lievens” in Liber Amicorum Dorine van Sasse van Ysselt, Charles Dumas (ed.), The Hague, Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie, 2011, pp. 51-55.

6 Bernhard Schnackenburg, trad. Kristin Lohse Belkin, Jan Lievens: Friend and Rival of the Young Rembrandt with a Catalogue Raisonné of His Early Leiden Work 1623-1632, Petersberg, Michael Imhof Verlag, 2016, cat. 98, pp. 281-282 and cat. 100, p. 283.

7 Ibid., p. 102.

Jan Lievens, Saint Peter, black chalk, white chalk highlights, 296 x 182 mm, Vienna, Albertina Museum, inv. 8906. © The Albertina Museum, Vienna.

Massimo Stanzione

THE SEVEN ARCHANGELS AT THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART

MASSIMO STANZIONE

Orta di Atella (Caserte), 1585-1656, Naples

THE SEVEN ARCHANGELS (recto)

STUDIES OF AN ARCHANGEL AND A WIND GOD (verso)

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, traces of black chalk (recto)

Pen and brown ink (verso)

195 x 358 mm

Inscribed on the back.

According to Bernardo de Dominici, Massimo Stanzione learned his trade in the Neapolitan atelier of Fabrizio Santafede, specialising initially in portrait painting. In 1621, Stanzione was made a Knight of the Golden Fleece and a Count Palatine by Pope Gregory XV, and in 1627 a Knight of the Order of Jesus Christ by Urban VIII, which would seem to be recognition of his early success as a painter. Yet his first forty years of activity remain fairly poorly documented. Indeed, although there are references to works prior to the 1620s, very few are extant. From the 1630s onwards, Stanzione was involved in most of the major projects in Naples. He then became one of the most important artists in Naples alongside Jusepe de Ribera, whose antithesis he is held to be in terms of style.

Although sources seem to indicate that Stanzione used drawings as a model and made drawings himself, Sebastian Schütze maintains that there are no more than twenty or so drawings in his entire oeuvre.1 In fact, if we discount attributions, whether stylistic, traditional or based simply on an old inscription, the number of sheets corresponding to known works by the artist, and which might be said to constitute a reliable corpus, could be counted on the fingers of one hand. The most remarkable work in this small group is without doubt Saint Bruno in Glory in the Musée de Poitiers; it was first published in 1992 and, in spite of many differences, is thought to be a preparatory drawing for the decoration of the dome of the Chapel of Saint Bruno in the Carthusian monastery of San Martino.2 There are also two other drawings that are stylistically coherent but whose connection with Stanzione’s work is more tenuous: A scene from the life of St Anthony, which relates to a documented, but now destroyed, decoration, and a Pietà, which was the foundation stone of the graphic corpus established by Walter Vitzthum, and relates to the work above the main portal of the church of the Carthusian monastery in San Martino.3 4

The Dormition of the Virgin, which is identical to a fresco in the Gesù Nuovo by Stanzione and fully accepted as by his hand, seems to us to be of lesser quality.5

The drawing we present here is a preparatory work for the painting of the same subject in the Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales in Madrid (ill. below). The painting was first attributed to the Spanish school, then to Francesco Guarino and finally to Stanzione by Maria Teresa Ruiz Alcón in 1974.6 Ruiz Alcón’s attribution is confirmed by Giuseppe Porzio, who dates the painting to the 1620s.7 The unpublished drawing of the seven archangels is a rare example of a direct relationship between painting and drawing and is therefore of great importance in understanding Stanzione’s graphic work. By capillary action, as it were, it enables a coherent group of pen-and-ink drawings to be attributed with greater confidence: Pietà, St. Magdalene Raptured by Angels, The Virgin and Child with St. Elizabeth and St. John the Baptist,and The Apparition of the Virgin and Child Holding the Cross to the Guardian Angel.8 9 10 11 On the reverse side, there is a study of a relatively complete figure − an even rarer phenomenon − with a readjustment to the angel’s right leg. The motif of the wind god, who is stiffer, could, as the sketchy pen-and-ink outline suggests, be a copy of a large ceiling decoration which the artist used to help reproduce the correct proportions of the model.

The Cleveland Museum of Art has acquired Massimo Stanzione’s drawing in June 2025.

1 Sebastian Schütze, « Teoria e pratica del disegno napoletano e l’arte del Cavalier Massimo » in Le Dessin napolitain, proceedings of the international conference (Paris, École Normale Supérieure, 6-8 March 2008), Francesco Solinas and Sebastian Schütze (dir.), Rome, De Luca Editori d’Arte, 2010, p. 83. According to de Dominici, Stanzione acquired a collection of drawings by the Bolognese masters of the Carracci school from Santafede.

2 Poitiers, Musée Sainte-Croix, inv. 882-1-421. See ibid., p. 84, repr. fig. 5, works cited n. 25, p. 90.

3 Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst, inv. GB 449. See ibid., pp. 84-85, repr. fig. 6, p. 84, works cited n. 26, p. 90.

4 Paris, formerly Janusz Zarnowski Collection. See ibid., p. 84, repr. fig. 3, p. 83, works cited n. 22, p. 90. A significant difference is the absence of the Carthusian monks in the drawing, as opposed to the fresco. This iconographic element is of fundamental importance when one considers the destination of the final work.

5 Naples, Museo nazionale di Capodimonte, inv. GDS 1054. See ibid., p. 84, repr. fig. 4, p. 83, works cited n. 23, p. 90.

6 Riccardo Lattuada, Francesco Guarino da Solofra: nella pittura napoletana del Seicento (1611-1651), Naples, Paparo Edizioni, 2000, cat. E12, pp. 185-186, repr., previous works cited; Maria Teresa Ruiz Alcon, « Los Arcángelos en los Monasterios de las Descalzes Reales y de la Encarnacion », Reales Sitios, XL, 1974, pp. 45-56.

7 De Caravaggio a Bernini: obras maestras del Seicento italiano en las colecciones reales de Patrimonio Nacional, exh. cat., Gonzalo Redín Michaus (dir.), Madrid, Palacio Real, 6 June-16 October 2016, Madrid, Patrimonio Nacional|Fundación Banco Santander, 2016, cat. 60, pp. 278-281.

8 Pietà, cf n. 4.

9 St. Magdalene Raptured by Angels, Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. INV9754. See Schütze, 2010, p. 86, repr. fig. 13, p. 87.

10 The Virgin and Child with St. Elizabeth and St. John the Baptist,Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. INV9826. See Schütze, 2010, op. cit., repr. fig. 9, p. 85.

11 The Apparition of the Virgin and Child Holding the Cross to the Guardian Angel, Orléans, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv. 168 (album 3.312). Attribution of the drawing alternates between Stanzione and Micco Spadaro. See Splendeurs baroques de Naples. Dessins des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, exh. cat., Poitiers, musée Sainte-Croix, 25 octobre 2006-4 février 2007, Catherine Loisel (dir.), Montreuil, Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2006, cat. 16, pp. 50-51, repr.

Massimo Stanzione, The Seven Archangels, oil on canvas, 2410 x 4000 mm, Madrid, Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales, Patrimonio Nacional, inv. 00610873. © Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica.

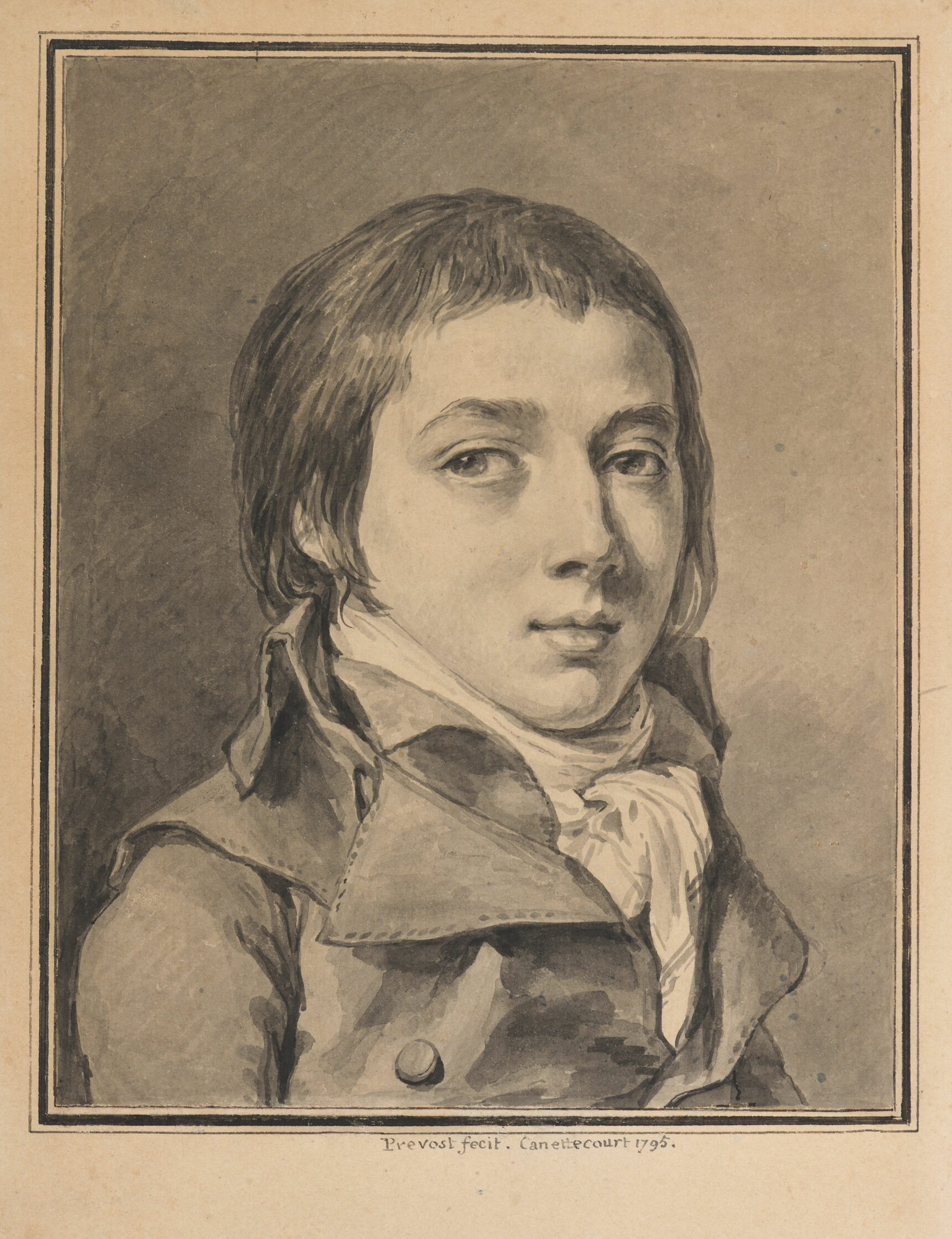

Bonaventure Louis Prévost

PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG BOY AT THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART IN NEW YORK

BONAVENTURE LOUIS PRÉVOST

Paris, 1733-1816

PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG BOY

1795

Grey ink (using the tip of the brush), grey wash

175 x 140 mm [the composition]

225 x 165 mm [the sheet]

Signed, localised and dated under the framing line: “Prevost fecit. Canettecourt 1795.”

Official records are the only documents that mention the actual first name of “B. L. Prevost”, as the engraver signed his plates. It was “Bonaventure Louis” and not “Benoît Louis”, as he was dubbed by Georg Kaspar Nagler and Louis Le Blanc, as well as most subsequent commentators. Furthermore, Prévost’s post-death inventory dates from 30 March 1816 and the death and inheritance tables of the city of Paris indicate that he died on 19 March 1816 at the age of 83, contrary to the details given in most biographical dictionaries.1

With the help of a few quotations, we can draw a brief portrait of Bonaventure Louis Prévost, engraver, draughtsman, print dealer and collector. In his catalogue of the work of Charles Nicolas Cochin, for whom Prévost was the engraver of choice, Charles-Antoine Jombert states that “he also acquired various other plates that form part of the work of M. Cochin fils, & which he is selling together or separately, for the convenience of collectors.”2 His activity as a dealer, the scale of which is difficult to quantify, probably enabled Prévost to assemble a handsome collection of prints. For the most part these were etchings by painters, as Prévost was “convinced that an etching engraved by the artist himself can be likened to a drawing in which the artist has preserved the first draft of his ardent imagination, and fixed, as it were, the rapid flight of his thought.”3 This collection, along with a few paintings, more than two hundred drawings – some from the Crozat, Gouvernet, Mariette and Lempereur collections – as well as a number of books, were offered for sale in January 1810, probably at the time when he was making arrangements for his estate.4 5

As the title of that sale indicates, Prévost was also a draughtsman and not just an engraver, although the latter activity seems to have been predominant. In particular, he engraved the famous frontispiece to Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie after a drawing by Cochin, of which there are two versions, one completed in 1772, the other in 1775.6 He also engraved plates of drawings by Moreau le Jeune for the Encyclopédie (in particular for the chapter in volume III devoted to “drawing”, for which Prévost also wrote the commentaries) as well as vignettes, for example for Desormeaux’s Histoire de la Maison de Bourbon, a substantial illustrated book, which also featured work by Boucher, Fragonard, Vincent and Choffard.

Prévost excelled in “small engravings”, the precision of his burin enabling him to accurately transcribe every detail of a composition despite the constraints of a small format. That is how he was described in a 1776 Almanach devoted to the arts, where he was also credited with being a “proper and elegant draughtsman”.7 An echo of the “refined and sensitive tact” with which he seems to have been gifted.8

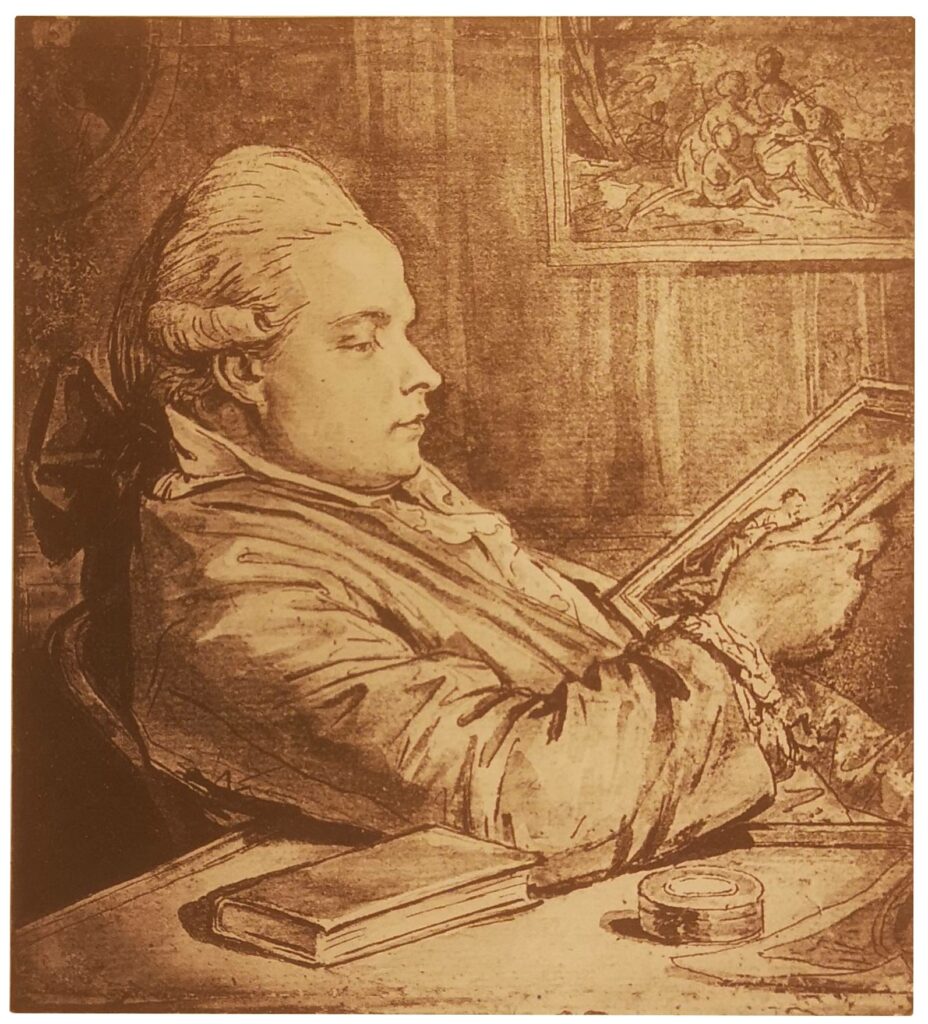

In parallel with his engraving work, Prévost also worked as a draughtsman-portraitist, as testified by a dozen surviving sheets. The only exception is the equestrian statue of Louis XV after Edmé Bouchardon, in pen and grey ink, dated 1764, a preparatory drawing for a plate reproduced in a book, published in 1768, by Pierre Jean Mariette on the making of the same statue.9 Although there is a pair of portraits in profile drawn in black chalk, in the manner of Cochin, the other drawings are in pen and grey ink, sometimes retouched with black chalk. Among them, Prévost’s tribute to his friend, the publisher and print dealer Jacques François Chéreau, engraved in aquatint by Antoine Carrée (ill. below), ought to be the most famous.10 11 In fact, Prévost sometimes seems only ever to use the tip of the brush, as is the case in our portrait of a young boy, in stark contrast to his practice as an engraver, but nonetheless with the same acute sense of light and shade. It was almost certainly this sensitivity – which will have been evident from the comments above – that established his discreet reputation as a portraitist.

Bonaventure Louis Prévost, Portrait of Jacques François Chéreau, circa 1780, pen and grey ink, grey wash, 170 x 150 mm, present location unknown. © Rights reserved.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has acquired Bonaventure Louis Prévost’s portrait during our March 2024 exhibition of Old Master and 19th-century drawings.

1 Jeffares, 2006. Nevertheless, the author does not specify either the location or the reference number of the archive items in question. Post-death inventory: Paris, Archives nationales, minutes et répertoires du notaire Henri Simon Boulard, MC/ET/LXXIII/1251 (MC/RE/LXXIII/22).

2 Charles-Antoine Jombert, Catalogue de l’œuvre de Ch. Nic. Cochin fils, écuyer, chevalier de l’ordre du Roy, censeur royal, garde des desseins du cabinet de sa Majesté, secrétaire & historiographe de l’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, Paris, Laurent François Prault, 1770, p. 77.

François Léandre Regnault-Delalande, Catalogue raisonné d’estampes anciennes et modernes, de peintre et de graveurs célèbres des écoles d’Italie, de Flandres, de Hollande, d’Allemagne, d’Angleterre et de France, quelques recueils, livres à figures et sur les arts, tableaux et dessins, du cabinet de Mr Prévost, dessinateur et graveur, Paris, François Léandre Regnault-Delalande, 1809 [Lugt 7685], p. i.

3 François Léandre Regnault-Delalande, Catalogue raisonné d’estampes anciennes et modernes, de peintre et de graveurs célèbres des écoles d’Italie, de Flandres, de Hollande, d’Allemagne, d’Angleterre et de France, quelques recueils, livres à figures et sur les arts, tableaux et dessins, du cabinet de Mr Prévost, dessinateur et graveur, Paris, François Léandre Regnault-Delalande, 1809 [Lugt 7685], p. i.

4 Ibid., p. iij.

5 Benjamin Peronnet, Burton B. Fredericksen, Répertoire des tableaux vendus en France au XIXe siècle. Volume I, 1801-1810, t. 1, Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Trust, 1998, n° 227, p. 68.

6 Christian Michel, Charles-Nicolas Cochin et le livre illustré au XVIIIe siècle. Avec un catalogue raisonné des livres illustrés par Cochin (1735-1790), Genève, Librairie Droz, 1987, n° 126, pp. 283-288.

7 Abbé Le Brun, Almanach historique et raisonné des architectes, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs et cizeleurs : contenant des notions sur les cabinets des curieux du royaume, sur les marchands de tableaux, sur les maîtres à dessiner de Paris, & autres renseignemens utiles relativement au dessin. Dédié aux amateurs des arts, Paris, [s. e.], 1776, p. 177. Neil Jeffares’ reference (cf. n. 1) to a certain “Prevost l’aîné”, who “also painted portraits very well” (p. 138), applies in our opinion to another artist, also a flower painter, who worked not far from his wife, a painter of miniatures, in the area around the Portes Saint-Martin and Saint-Denis (pp. 116 and 120).

8 Regnault-Delalande, 1809, op. cit., p. ij.

9 Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des Estampes et de la Photographie, inv. RES QB-201 (105)-FOL, fol. 37, Hennin 9162 (facing p. 161).

10 Collection Jean Masson, sale of, Paris, Galerie Petit, 7 and 8 May 1923, lots 192 and 193. The first is dated 1771.

11 Collection Paul Mathey, sale of, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 18 May 1901, lot 60 (last known location).

VINCENZO

GEMITO

PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GIRL

AT THE MUSÉE D’ORSAY

VINCENZO GEMITO

Naples, 1852-1929

PORTRAIT OF A YOUNG GIRL

1917

Black chalk, graphite, gouache, watercolor, black ink, white chalk

555 x 365 mm

Signed and dated bottom left: «GEMITO./1917».

Vincenzo Gemito’s was born from unknown father and mother. The day after his birth, he was left on the steps of the Real Casa Santa dell’Annunziata, a church that took in abandoned children. He was then adopted by Giuseppina Baratta, whose second husband, Francesco Jadiccio, who Gemito called Masto (or Mastro) Ciccio, became not only his adoptive father but also, years later, his assistant in casting bronzes. His childhood and adolescence were marked by poverty and a hard life. The many portraits of young models he met on the streets reflect his everyday surroundings, an attention to life that he will always cherish. At thirteen years old, he met Antonio Mancini, they both enrolled at the Istituto di Belle Arti, Mancini studying painting, Gemito studying sculpture, under the tuition of Domenico Morelli. Gemito soon made his mark and began exhibiting at the Società Promotrice di Belle Arti in 1870. In Paris, he presented the bronze of Il Pescatorello (“The Neapolitan Fisherboy”). It was exhibited at the third Paris World’s Fair in 1878 and met with great success. From then on, despite the tragic loss of people dear to him − Mathilde Duffaut in 1878, then, in 1904, his wife Anna Cutolo, who ran the foundry he had constructed in 1883 − and despite psychological instability, Gemito regularly exhibited bronzes that enjoyed a certain fame.

Although he practised drawing throughout his career, Gemito spent more time on this practice during the last thirty years of his life. He worked with chalks rather than with pen and ink, mixing techniques liberally. Apart from commissions from public figures, he drew numerous portraits of the people around him, mainly his nieces, or female models he had seen in Naples neighbourhoods and in the countryside. Gemito was particularly attentive to volume and shape which he brought out with light and shadow, thus intensifying the physical presence of his subjects.

This portrait of a girl, with dishevelled hair and a rebellious air, is a kind of counterpoint to the portrait, executed a year earlier, of his niece Anita with her hair neatly tied up with a striped bow. Gemito belongs in the tradition of verismo portraits of ordinary people; the exaltation of their raw, unadorned beauty places him in the tradition of 17th-century Neapolitan naturalism.

The Musée d’Orsay has acquired Vincenzo Gemito’s “Portrait of a Young Girl” during our June 2023 exhibition of Neapolitan drawings from 17th to 19th century.